Re: November

2002 issue of Classic Bike.

On page 65 you have a very interesting article on motor pacing at Herne

Hill. Our Cycling club is based there and our members would be very

interested in the article. Would it be possible for me to obtain

permission to copy said article to our website?

Mike Peel

Yes, you can put the

article on the website so long as Classic Bike is prominently credited: 'Feature

reproduced by permission of Classic Bike magazine - November 2002 issue'

Regards

Becky Cornell

Editorial Assistant

|

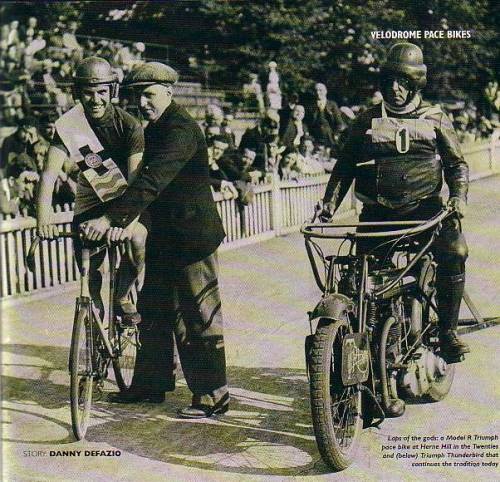

Laps of the gods: a model R Triumph pace bike at Herne Hill

in the Twenties and (below) Triumph Thunderbird that continues the

tradition today

|

Story by Danny Defazio

|

ARE STILL

GO

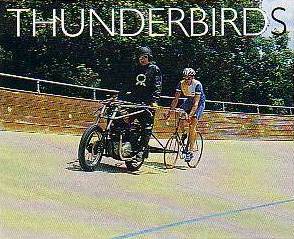

... but for how much longer? Modified TR65 Triumphs

are continuing a long tradition by acting as pace bikes for cycling racing

at the last velodrome in London. But its days may be numbered as the local

council threatens to wave the final chequered flag… |

When London staged the Olympic Games in 1948, more than

48,000 people packed into the Herne Hill Velodrome to watch the cycle track

disciplines. Fast forward 54 years and 1 am greeted by blank looks and the

shaking of heads when 1 ask directions to the venue that still stages cycle

events.

The evidently little known Herne Hill track, in south east

London, is the last remaining velodrome in the whole of the Greater London area

and the south east. And there is now a question mark over its future the local

council is undertaking various feasibility studies and there is talk of cycling

giving way to football. A final decision will be made in October, 2003.

So 1 had better get a move on. I am here in Herne Hill to

try out one of the ten 1982 Triumph TR65 Thunderbirds used as pace bikes.

Pace bikes in the sense that the ten Thunderbirds stay on

the track for the entire race, getting their pursuing charges up to racing speed

and then adjusting accordingly.

It makes for the extraordinary spectacle of up to ten

motorcyclists and ten cyclists haring around the velodrome, with the spoils

going to the first, hard-pedalling cyclist and Thunderbird 'driver', as the

Triumph riders are called, to cross the line.

|

|

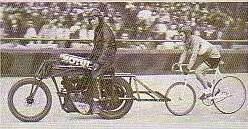

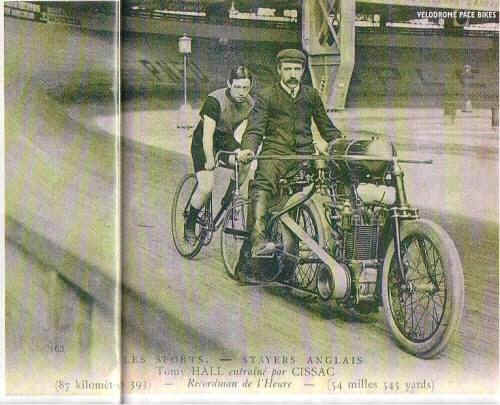

| Above:

Twenties velodrome action on the Continent

Right: frame with roller

prevents cyclists from jamming into the pace bike

Below: this heavyweight

machine in action on the Continent |

And a Thunderbird in the sense that, at first glance, the

machine 1 am given to try out certainly looks like a Thunderbird and,

notwithstanding the absence of any form of baffling, it sounds like a familiar

Meriden twin. But when you actually start to ride this adapted machine, you

quickly realise that a good part of what knowledge you have acquired about

motorcycling is of little use.

For

a start, you straddle the bike rather than sit on it. There isn't a seat...

well, not one worthy of its name. Instead, there is a rump shaped panel.

For

a start, you straddle the bike rather than sit on it. There isn't a seat...

well, not one worthy of its name. Instead, there is a rump shaped panel.

But then, with this machine you are forced to either stand

on the ground or on the footplates. Making the transition from one to the other

is the catch.

Fortunately I have 57 year old Colin Denman, one of the

three coaches at the track, as host for the day. He explains that the secret of

getting safely airborne is to have someone hold the back end of the bike and

give you a running start, while you perch on that absurd panel and work out

which way you are planning to wind the throttle. After all, you do have a

choice.

Professional pace riders know that every wisp of air

flowing beneath their underarms is literally a drag to the following cyclist,

which is why a crude mechanism allows them to turn the throttle in reverse. This

means that their arms are pinned tight against their, bodies.

However, when you are standing on the hot seat and hanging

on to those absurdly long handlebars, you revert to being a slave to convention

and wind up the throttle as normal anti clockwise. Thankfully this is only a

practice run. It would be a different ball game in competition.

Then, you suddenly notice that the gear lever is on

backward, so the sequence is one up, three down. As for fifth, forget it. It is

not on any of the bikes. Colin does not know why.

A short stroke (76 x 71.5mm) torquey twin, the 65Occ

machine is as forgiving as Hillary Clinton, and soon you are wobbling your way

to the first embankment. You could imagine them all sniggering behind on the

terraces but you are too busy trying to work out the laws of physics to worry

about image. The huge rear sprocket demands that you shift up rapidly, and soon

you and the bike are climbing the wall. Instantly, you begin to reappraise

gravity and realize just what a big baby you are.

| Triumph's sporting

links

Launched in 1981 two years before the collapse of

Meriden the Triumph Thunderbird was an economy 649ce motorbike, priced at

£200 less than the Bouneville. Only 400 machines were made and the marque

was largely forgotten until a mini revival of interest in recent years

(see the feature in December 2001 issue of CB).

The Thunderbirds are not the first Triumph links

with the sport. Way back in the twenties, ranks of pace bikes that can

best be described as Model R Roadsters were roaring round the velodromes

of Europe. leading generations of .

One of the more impressive sights must have been the

huge three litre V-twin Anzani-powered pace bike that enabled Leon

Vanderstuyft to set a 76mph speed record at the Montlhery circuit south of

Paris in 1925.

At the other end of the scale are the 90cc two

stroke Puch-engined Derny practice pace bikes that are still in regular

use today. |

It is surprisingly sticky and tractable up there, and now

the Thunderbird is roaring around the perimeter, seemingly finding its own

track.

The ride is firm to painful thanks to the considerable

vibration, and it feels as if you need to take a pipe wrench to the steering.

The problem could be the lack of rear shockers, but suspicion soon falls on the

gearing. Also, the extra unsprung weight cannot be helping and you are glad

there are not potholes on the track, otherwise you would be brought down fast.

By the end of the first lap, you are beginning to get the

hang of it. You are still wobbling like a Sumo wrestler but at 40mph plus, it is

not that noticeable.

There is no foot brake you would not be able to use one

standing up, as it would simply pitch you over the headstock. Instead, you have

two levers on the left handlebar. One is for the clutch, the other is the rear

brake that operates the standard Thunderbird drum. On the opposite side is a

familiar Lockheed master cylinder.

Not that you actually need brakes. Well, not when you are

out joyriding. But when there are ten pace bikes on the track as there sometimes

are, each being pursued by a sweaty and frantic rider hurtling close behind, a

totally different level of skill is required.

The Thunderbirds were housed originally at the Leicester

Velodrome and were supplied and converted by an unknown dealer for the 1982

British Cycling Federation world championships. When the Leicester track was

demolished, the bikes were tried at the Manchester Velodrome, but were too heavy

for the wooden track, so they were sent to Herne Hill, where they reside in

articulated truck containers.

The conversion from motorcycle to pace bike may look

clumsy, but it works and follows a style forged by a century of experience.

The rear angle Iron frame carries a roller to prevent the

cyclist from jamming into the pace bike. The roller is set at a regulation

distance, and the good paceman knows exactly how to keep his rider out of the

breeze and on the fastest line.

"It is quite a knack," admits Colin. "But

we are in constant contact simply by shouting at each other, and you develop

strategies to stay ahead."

Quite, but some would go further and say it is the paceman

who is the real lynchpin of the race. After all, any fool with a pair of huge

calves can pedal a pushbike. Guiding that same fool through a roaring melee of

eight equally determined teams is as much an art as a science.

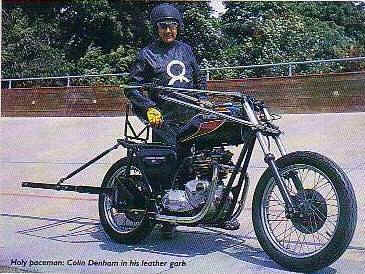

| 'Batman' stars at the

velodrome

You might well ask why Colin Denham rides his

Tunderbird in fancy dress. In fact, it is not a Batman costume but a suit

made for the 1982 world championships. Never a sport that attracts

much money, and so the suits have yet to be replaced. The sport may

be short of cash but it is a tough sport. Speeds of 70mph are not

uncommon and there are tales of dirty tricks and sabotage, but acid

attacks on riders could be folklore. However, there have been

fatalities. During WW2 an RAF man fitted his own carburettor to a

pace bike and flew over the embankment, breaking his neck.

Colin

has had his share of injuries, including three broken ribs that resulted

in a three-month lay-off. "The biggest danger is a tyre

blow-out," he says. "These tyres, which are taped and

gluded to the rims, operate under enormous loads. One bike can, and

frequently does, bring down everything else behind it." Colin

has had his share of injuries, including three broken ribs that resulted

in a three-month lay-off. "The biggest danger is a tyre

blow-out," he says. "These tyres, which are taped and

gluded to the rims, operate under enormous loads. One bike can, and

frequently does, bring down everything else behind it."

Communication between driver and rider is

rudimentary. Intercoms were tried but aborted, so it is back to

shouting - "Allez" for Get on with it, and "Whoah!"

for slow down.

A cyclist since 1955 and a motorcyclist since not

long afterwards, Colin has a Category A British Cycling Federation licence

that allows him to ride anything on the track, and he keeps fit by cycling

50 miles a week. Now he fears for the future at Herne Hill.

Not only has there been no racing this year because of lack of riders but

there is the threat of a council redevelopment. |

|

Colin

Denman drove this 90cc two stroke to win the National Championship

this year with fellow Herne Hill coach Russell Williams |

|

|